Thebe (moon)

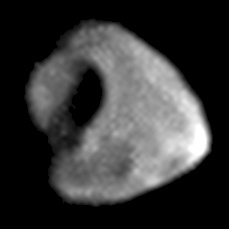

Image of Thebe taken by the Galileo spacecraft on January 4, 2000.

|

|

|

Discovery

|

|

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Stephen P. Synnott / Voyager 1 |

| Discovery date | March 5, 1979 |

| Periapsis | 218,000 km[1] |

| Apoapsis | 226,000 km[2] |

| Mean orbit radius | 221889.0 ± 0.6 km (3.11 RJ)[3] |

| Eccentricity | 0.0175 ± 0.0004[3] |

| Orbital period | 0.674536 ± 0.000001 d (16 h 11.3 min)[3] |

| Inclination | 1.076 ±0.003° (to Jupiter's equator)[3] |

| Satellite of | Jupiter |

|

Physical characteristics

|

|

| Dimensions | 116×98×84 km[4] |

| Mean radius | 49.3 ± 2.0 km[4] |

| Volume | ~500,000 km³ |

| Mass | 4.3 × 1017 kg[5] |

| Mean density | 0.86 g/cm³ (assumed) |

| Equatorial surface gravity | 0.013 m/s² (0.004 g)[4][6] |

| Escape velocity | 20–30 m/s[7][8] |

| Rotation period | synchronous |

| Axial tilt | zero |

| Albedo | 0.047 ± 0.003[9] |

| Temperature | ~124 K |

Thebe (pronounced /ˈθiːbi/ THEE-bee, or as in Greek Θήβη), also known as Jupiter XIV, is the fourth of Jupiter's moons by distance from the planet. It was discovered by Stephen P. Synnott in images from the Voyager 1 space probe taken on March 5, 1979, while orbiting around Jupiter.[10] In 1983 it was officially named after the mythological nymph Thebe (Greek mythology).[11]

Thebe orbits within the outer edge of the Thebe Gossamer Ring that is formed from dust ejected from its surface.[7] Thebe is the second largest of the inner satellites of Jupiter. Thebe is irregularly shaped and reddish in colour, and is thought like Amalthea to consist of porous water ice with unknown amounts of other materials. Its surface features include large craters and high mountains—some of them are comparable to the size of the moon itself.[4]

Thebe was photographed in 1979 and 1980 by the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, and later, in more detail, by the Galileo orbiter in the 1990s.[4]

Contents |

Discovery and observations

Thebe was discovered by Stephen P. Synnott in images from the Voyager 1 space probe taken on March 5, 1979, and was initially given the provisional designation S/1979 J 2.[10][12] In 1983 it was officially named after the mythological nymph Thebe who was a lover of Zeus—the Greek equivalent of Jupiter.[11]

After its discovery by Voyager 1, Thebe was photographed by Voyager 2 spaceprobe in 1980.[7] However, before the Galileo spacecraft arrived at Jupiter, knowledge about it was extremely limited. Galileo imaged almost all of the surface of Thebe and put constraints on its composition.[4]

Orbit

Thebe is the outermost of the inner Jovian moons, and orbits Jupiter at a distance of about 222,000 km (3.11 Jupiter radii). Its orbit has an eccentricity of 0.018, and an inclination of 1.08° relative to the equator of Jupiter.[3] These values are unusually high for an inner satellite and can be explained by the past influence of the innermost Galilean satellite, Io;[7] in the past, several mean motion resonances with Io would have passed through Thebe's orbit as Io gradually receded from Jupiter, and these excited Thebe's orbit.[7]

The orbit of Thebe lies near the outer edge of the Thebe Gossamer Ring, which is composed of the dust ejected from the satellite. After ejection the dust drifts in the direction of the planet under the action of Poynting-Robertson drag forming a ring inward of the moon.[13]

Physical characteristics

Thebe is irregularly shaped, with the closest ellipsoidal approximation being 116×98×84 km. Its bulk density and mass are not known, but assuming that its mean density is like that of Amalthea (around 0.86 g/cm³),[4] its mass can be estimated at roughly 4.3 × 1017 kg.

Similarly to all inner satellites of Jupiter, Thebe rotates synchronously with its orbital motion, thus keeping one face always looking toward the planet. Its orientation is such that the long axis always points to Jupiter.[7] At the surface points closest to and furthest from Jupiter, the surface is thought to near the edge of the Roche lobe, where Thebe's gravity is only slightly larger than the centrifugal force.[7] As a result, the escape velocity in these two points is very small, thus allowing dust to escape easily after meteorite impacts, and ejecting it into the Thebe Gossamer Ring.[7]

The surface of Thebe is dark and appears to be reddish in color.[9] There is a substantial asymmetry between leading and trailing hemispheres: the leading hemisphere is 1.3 times brighter than the trailing one. The asymmetry is probably caused by the higher velocity and frequency of impacts on the leading hemisphere, which excavate a bright material (probably ice) from the interior of the moon.[9] The surface of Thebe is heavily cratered and it appears that there are at least three or four impact craters that are very large, each being roughly comparable in size to Thebe itself.[7] The largest (diameter about 40 km) crater is situated on the side that faces away from Jupiter, and is called Zethus (the only surface feature on Thebe to have received a name).[7][14] There are several bright spots at the rim of this crater.[4]

References

- ↑ Calculated as a×(1 − e), where a is semimajor axis and e is eccentricity.

- ↑ Calculated as a×(1 + e), where a is semimajor axis and e is eccentricity.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Cooper, N.J.; Murray, C.D.; Porco, C.C.; Spitale, J.N. (2006). "Cassini ISS astrometric observations of the inner jovian satellites, Amalthea and Thebe". Icarus 181: 223–234. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.11.007. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006Icar..181..223C.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Thomas, P.C.; Burns, J.A.; Rossier, L.; et al. (1998). "The Small Inner Satellites of Jupiter". Icarus 135: 360–371. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5976. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1998Icar..135..360T.

- ↑ Estimate is based on the known volume and assumed density of 0.86 g/cm³.

- ↑ The estimate from Thomas, 1998 was divided by 1.5 to account for the difference in assumed densities.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Burns, J.A.; Simonelli, D. P.;Showalter, M.R. et al. (2004). "Jupiter’s Ring-Moon System". In Bagenal, F.; Dowling, T.E.; McKinnon, W.B. (pdf). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. http://www.astro.umd.edu/~hamilton/research/preprints/BurSimSho03.pdf.

- ↑ The estimate from Burns, 2004 was divided by 1.5 to account for the difference in assumed densities.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Simonelli, D.P.; Rossiery, L.; Thomas, P.C.; et al. (2000). "Leading/Trailing Albedo Asymmetries of Thebe, Amalthea, and Metis". Icarus 147: 353–365. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6474. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000Icar..147..353S.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Synnott, S.P. (1980). "1979J2: The Discovery of a Previously Unknown Jovian Satellite". Science 210 (4471): 786–788. doi:10.1126/science.210.4471.786. PMID 17739548. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1980Sci...210..786S.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn (IAUC 3872)". 30 September 1983. http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/iauc/03800/03872.html. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ↑ "Satellites of Jupiter (IAUC 3470)". International Astronomical Union. 28 April 1980. http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/iauc/03400/03470.html. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ↑ Burns, J.A.; Showalter, M.R.; Hamilton, D.P.; et al. (1999). "The Formation of Jupiter's Faint Rings". Science 284 (5417): 1146–1150. doi:10.1126/science.284.5417.1146. PMID 10325220. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999Sci...284.1146B.

- ↑ "Thebe Nomenclature:craters". United States Geological Union. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/jsp/FeatureTypesData2.jsp?systemID=5&bodyID=25&typeID=9&system=Jupiter&body=Thebe&type=Crater,%20craters&sort=AName&show=Fname&show=Lat&show=Long&show=Diam&show=Stat&show=Orig. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||